Drowning in Science

The Supreme Court has, indirectly, chided Congress for failure to do their job by passing off hard jobs to the regulatory agencies (WEST VIRGINIA ET AL. v. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY ET AL.) Congress often enacts general and somewhat vaguelaws and leaves the agencies to promulgate regulations that are based on complicated scientific and economic issues. Once Congress has finished with their part (legislation), they don’t do much to monitor the agencies (regulation).

But now the Supreme Court has sent Congress back to the old days where the laws are actually supposed to govern, as opposed to just passing a fuzzy baton to the administrative state. The first regulatory agency was established 150 years ago by President Lincoln in 1862, the U.S. Department of Agriculture. FDA was established 116 years ago in 1906 and EPA in 1970. And even since 1970, things have changed.

As one paper puts it,

“In the past century, the academic publishing world has changed drastically in volume and velocity [1]. Along with the exponential increase in the quantity of published papers, the number of ranked scientific journals has increased to >34,000 active peer-reviewed journals in 2014 [1], and the number of published researchers has soared [4].”

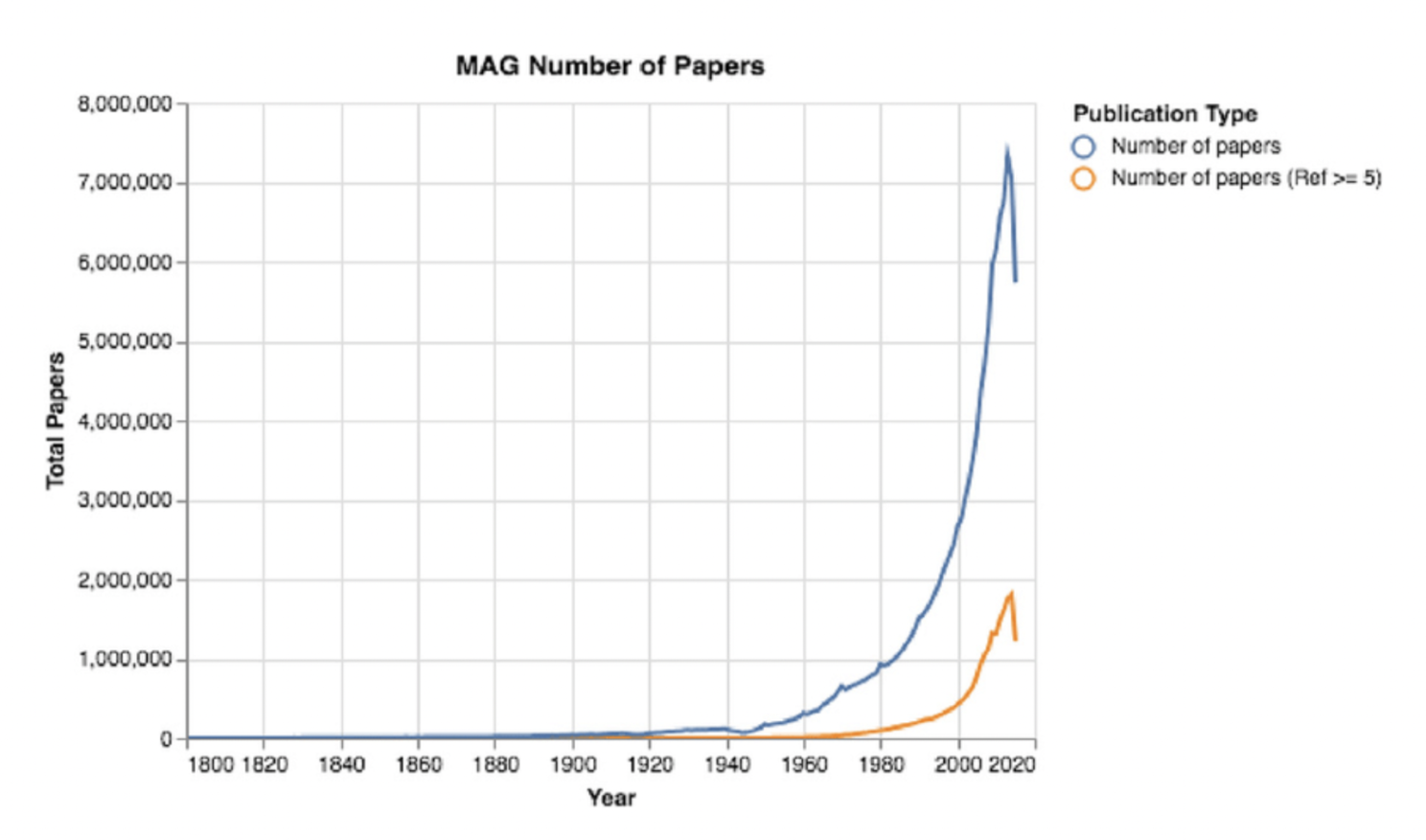

Using a Microsoft data set, it’s easy to see how the number of scientific papers has grown (the decline in 2014 was attributed to some missing papers in the data set).

What does that have to do with Congress taking on the job of passing sensible laws, particularly related to science?

Suppose Congress wants to pass legislation on global warming and fossil-fuels. In Google scholar, a search for global warming and fossil fuels turns up 488,000 papers. If they want to address obesity, there are 3.3 million papers listed. Suppose they are looking into making COVID masks mandatory. They have to contend with 117,000 papers.

Of course, the agencies have these problems too but at least they have some scientists dedicated to the problems. But the problem is even worse than just the sheer numbers.

Some papers, mostly human studies (epidemiology), only find things that occur at the same time (correlation), but they don’t tell you about causation. Without causation, legislation may not be effective. Other papers are poorly designed, use fraudulent data, misuse statistics and, in general, aren’t reliable. Part of the sifting process then is to separate out the good and useful studies from the poor and unreliable ones.

That’s the problem. In order to do “good” evidenced-based lawmaking, or regulations for that matter, you have to go through a lot of evidence. Even with expert testimony and the Congressional Research Service, it may not be enough.

Here’s one promising possibility – artificial intelligence. In a paper published in 2020, authors at the Lawrence Berkeley National Lab hypothesize that, just on COVID-19, there were 500,000 papers published before the outbreak and hundreds coming out every day during the pandemic. That further note that, “Traditional methods of searching through the research literature just don’t cut it anymore.” So, they built a search engine to pick up relevant information, not to replace scientists, but to “help them gain new insights from more papers than they could read in a lifetime.”

Even beyond just searching for keywords and compiling information, AI may eventually power machines to be “… taught more scientific facts, [which] will be able to help scientists streamline their logical arguments; spot errors, inconsistencies, plagiarism, and duplications; and highlight connections.”

In short, we are now producing more knowledge, more quickly and are outpacing any organization’s ability to keep up and to produce well-sourced rules. Perhaps AI, and even machine learning, can help. In the end, it doesn’t matter whether it is Congress or the regulatory agencies, we need help.